JAPAN/TOKYO – Miwa Moriya was 6 when social workers told her she was going to a Christmas party, but have instead moved her into a group home for about 60 children in a small city in western Japan.

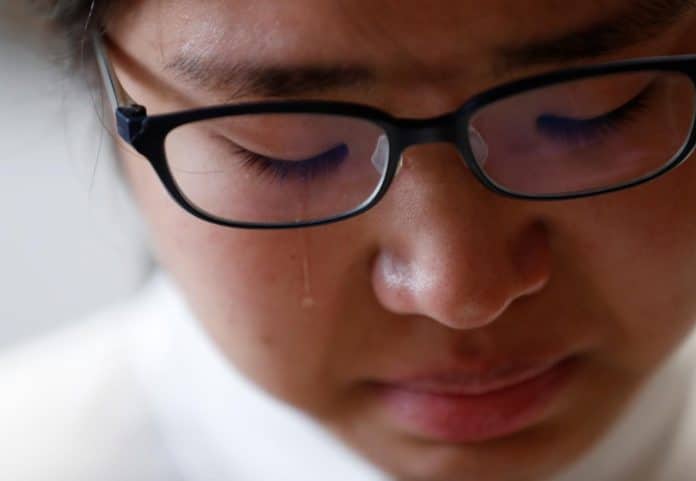

The “Christmas party” turned into more than eight years of living away from her mother, and the beginning of a long battle with loneliness, bullying, and trauma. She was never told exactly why she was sent to the home – only that the state thought she would be better off there than with her family.

Unlike most developed countries, which place the majority of children who are abused, neglected, or can’t live with their parents for other reasons in foster homes, Japan puts more than 80% of the 38,000 such children in residential-care facilities, according to government figures.

About one in seven children stay for more than a decade in such facilities, data show – despite UN guidelines that such children should grow up in a family setting.

The government has made the issue a legislative priority after several high-profile child-abuse deaths and a sharp rise in overall abuse cases. Local authorities have been given a deadline of next March to draw up a plan to improve the situation.

Last summer, the Japanese government said it wanted at least three-quarters of preschoolers in need of state care to live in foster homes within seven years, and the number of adoptions to double to at least 1,000 within five.

Hundreds of care facilities were set up after World War Two to shelter orphaned street children, and state care has largely been relegated to them since then. About 600 are operating today.

Such facilities – most of which house 20 or more children – have helped many, but are a poor alternative to a healthy family setting, experts say. A government investigation last month found sexual violence among children was widespread at such institutions.

“Everyone here says, ‘Children are important,’ but that’s false,” Yasuhisa Shiozaki, an influential lawmaker who has led efforts to improve children’s welfare in recent years, told Reuters. “Children have always taken a back seat to adults’ interests in Japan. That has to change.”